FULL TEXT

Resumen

Desde el comienzo del Neolítico, los seres humanos se han estado asentado en villas, pueblos y ciudades. El proceso de fundación, desarrollo decadencia y muerte (o renacimiento) de estos asentamientos siempre se ha analizado antropocéntricamente, pues se ha entendido que es el ser humano el factor determinante en el proceso histórico de los mismo. No obstante, estudios recientes han comenzado a reconocer que, en el proceso de urbanismo, el impacto de lo no – humano (orgánico, inorgánico o afectivo) tiene el mismo peso que las acciones de los seres humanos.

En el presente articulo utilizando el acercamiento del Nuevo Materialismo y la teoría de ensamblaje de Manuel De Landa, queremos hacer un acercamiento a la influencia de los elementos inorgánicos presentes en la Nueva Jerusalén revelada en Apocalipsis 21 – 22. Nos estaremos enfocando en el elemento material de las murallas de la Nueva Jerusalén celestial y cual es el efecto de estas en el ensamblaje de esta ciudad descendida de la pluma de Juan de Patmos.

Palabras Claves: Nueva Jerusalén, Teoría de los Ensamblajes, Nuevo Materialismo, Territorialización, Desterritorialización, Giles Deleuze, Manuel De Landa, Murallas, Puertas

New Jerusalem, Assemble!

An Application of Assemblage Theory to the New Jerusalem 1

Introduction

On his classic article on urbanism as a way of life, sociologist Louis Wryth argues against defining the city by its intensities or number of inhabitants.2 Anthropologist Timothy R. Pauketat agrees with Wirth when he argues that “cities and other less-bounded forms of urbanisms are more than just grouping of things. They are arrangements of immaterial or affective elements, qualities and movements as well.”3 Traditionally, these immaterial or affective elements have been comprehended in an anthropocentric sense.4 For example, Wirth gives the following definition of a city; “a city may be defined as a relative large, dense and permanent settlement of socially heterogeneous individuals”.5 Individuals here is to be understood as homo sapiens.

Another early twenty- century sociologist defines the city in the following fashion:

The city is, rather, a state of mind, a body of customs and traditions, and of the organized attitudes and sentiments that inhere in these customs and are transmitted with this tradition. The city is not, in other words, merely a physical mechanism and an artificial construction. It is involved in the vital processes of the people who compose it; it is a product of nature, and particularly of human nature.6

Though there is a recognition that immaterial phenomena have agency over the dynamics of the city, the emphasis has always been on the άνθρωπος, the human being.

Anthropocentrism in urban studies can be traced from Ernest W. Burguess’ concentric zones theory of the 1920’s, to David Harvey’s Marxist critique of capitalism and the city in the late Twenty and early Twenty-First centuries. From our research, it follows that an approach to ponder the non-human immaterial or affective elements, qualities and movements of the city is lacking. This is to the detriment of urban studies (in its many facets).

Not to discount the importance of human relations in the phenomena we call the city, but it is also important to hold in consideration the agency that non-human entities may also have on the city. Jane Bennett says it more eloquently:

It is important to follow the trail of human power to expose social hegemonies (as historical materialists do). But my contention is that there is also public value in following the scent of a nonhuman, “thingly” power, the material agency of natural bodies and technological artifacts.7

As demonstrated in Susan M. Alt and Timothy R. Pauketat’s edited book New Materialisms, Ancient Urbanisms; the tools used by the New Materialism approach8 can help bridge the gap created by anthropocentrism in urban studies.9 One of the main arguments of Altand Pauketat’s book is that non-human and even non-living elements had agency in the formation of ancient cities that were founded for religious purposes.10

Following the cue from New Materialisms, Ancient Urbanisms, we will attempt to do a new materialist analysis of the western prototype of a religious city, the New Jerusalem as described in the Christian Testament book of the Apocalypse or Revelation of John.11

In this paper we will apply a New Materialism analytic tool, assemblage theory, as developed by Manuel De Landa (based on the concept of assemblage of Giles Deleuze and Félix Guattari) to analyze this divine city. We understand that a new materialist analysis of the New Jerusalem is merited because, as Thomas W. Martin argues, Western civilization cities have been imagined and dreamed on the model of the New Jerusalem. 12 Or as stated by Catherine Keller “… the Bride City of the Apocalypse remains the most influential utopia in history.13 Assemblage TheoryThe term Assemblage is an important one in deleuzian-guattarian philosophy. 14 The term Assemblage appears at least 144 times in the first four chapters of Deleuze and Guattari’s book A Thousand Plateaus.15 Statistics aside, although, the concept of assemblage is preponderant in Deleuze and Guattari’s work, they did not elaborate a “Theory of Assemblage” per se.16 So, we are left with the question, what exactly does Deleuze and Guattari wish to convey with the term assemblage?

Manuel De Landa is known as one of the main interpreters of Delueze’s concept of assemblage.17, 18 De Landa affirms that the delueuzian concept of assemblage is to be applied to wholes that are formed by heterogenous parts.19 But besides that, De Landa argues that there is little else to sketch a deluzian theory of assemblage. Assemblage and its supporting concepts, like almost everything in the Deluzian canon is anything but systematic. As De Landa points out; “The definitions of concepts used to characterize assemblages are dispersed throughout Deleuze’s work: part of a definition may be in one book, extended somewhere else, and qualified later in some obscure essay.”20 However, De Landa argues that the supporting concepts around assemblage (“expression” or “territorialization”) are elaborated in Deleuze’s works as to provide a rough schematic framework for a theory of assemblage.21

De Landa argues that assemblages are characterized by two dimensions. The first dimension concerns the role components may play in the assemblage. These roles can be material, expressive or a mixture of the two. For example, in a social assemblage the material role of the component would be the bodies and artifacts through which material, physical interaction happens. While an example of an expressive role would be the non-linguistic communication that happens among the components.

The second dimension refers to the effect that the components have on either the stabilization or destabilization of the assemblage’s identity. This stabilizing or distabilizing function is refered by Deleuze as territorilization/deterritorialization. De Landa defines territorialization/deterritorialization in the following manner:

Territorialization, … refers to non-spatial processes which increase the internal homogeneity of an assemblage, such as the sorting processes which exclude a certain category of people from membership of an organization, or the segregation processes which increase the ethnic or racial homogeneity of a neighbourhood.

Any process which either destabilizes spatial boundaries or increases internal heterogeneity is considered deterritorializing.22, 23

Assemblage theory and the New Jerusalem

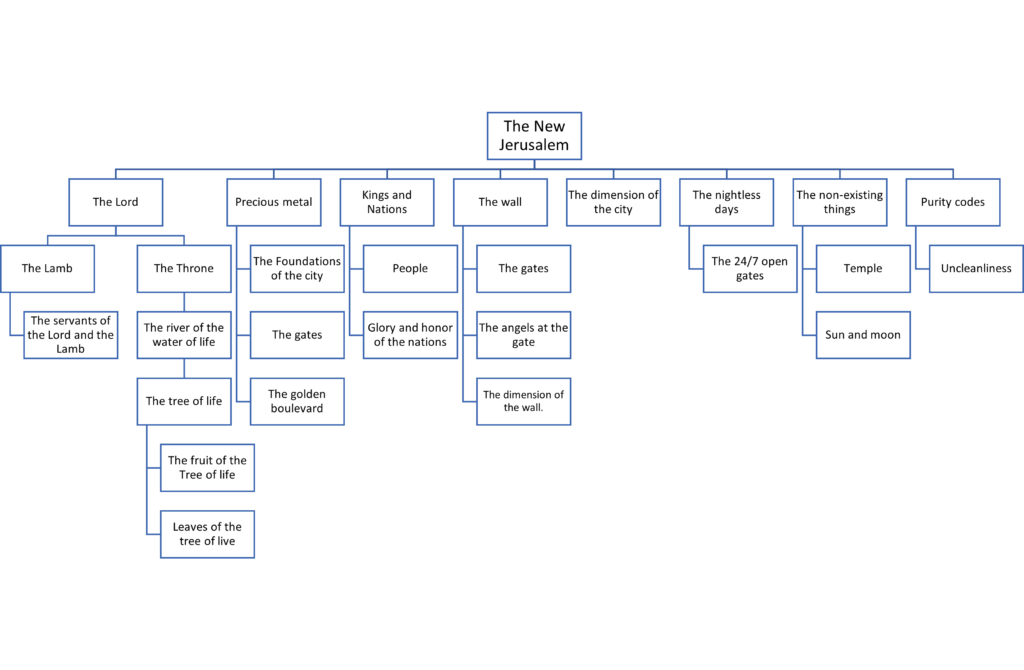

It can be argued ex-post facto that Jane Jacobs’ 1961 book Death and Life of Great American Cities is in part a description of the city as an assemblage.24 Jacobs scrutinize the elements that contribute or undermine great cities (sidewalks, mix-uses, prevalence of the automobile, etc.). Following Jacobs, we propose that the assemblage of the New Jerusalem is composed of the following components;

Figure 1: The Assemblage of the New Jerusalem25

In total, we have identified at least 29 elements that make up the assemblage of the New Jerusalem. Following our criticism of the anthropocentric study of cities, we will focus on a component that is neither human, nor a will possessing entity (God, the Lamb, and the Angels). We will analyze the walls of the of the New Jerusalem.26. Our analysis will attempt to answer the following two questions;

- What is the role that the city walls play in the assemblage (material, expressive or a mixture of the two)?

- How does the city walls territorialize or deterritorialize the assemblage?

The Role of the walls in the assemblage of the New Jerusalem

Stephen Moore has made the following comment about the New Jerusalem “As it happens, an impressively high wall bisects the final two chapters of Revelation. The book’s climactic vision is set in a divinely designed gated community, a heavenly walled enclave.”27 We find the connection between today’s gated communities very astute. First of all, as with gated communities nowadays, walls were a status symbol in the ancient world. David E. Aune comments that during the Roman Empire, walls were the highest expression of triumphal architecture, particularly in Greece and Asia Minor.28,29

The other connection that we can make between today’s gated communities and the New Jerusalem is that the walls are supposed to give a sense of security, in other words they are for defensive purposes.30 However, following the narrative of John of Patmos, at this stage all of the enemies of the Lamb and his followers have been vanquished. Thus the question of defense from what or from who is thrusted upon us. We will return to this later.

We can make a case that the walls of the New Jerusalem have both a material and expressive function in the formed assemblage. The materiality of the walls is patent in the description and measuring of the wall itself.31 On the other hand, as it can be argued just like the border wall being built between Mexico and the United States,32 a wall is not just a wall. The wall is in fact the materialization of two human needs, recognition and safety.

As mentioned above city walls were a status symbol for ancient cities, akin to the “sexy rail” fad or the convention center mania of the late twenty-century modern cities. However, as status symbol goes, the walls of the New Jerusalem are the mother of all status symbols.

Exegetes differ on whether the text says that the wall measures 1,500 miles (12,000 stadia)33, high or 216 feet34 (144 cubits). Others say that the height of the walls are not mentioned in the text, but that the 144 cubits figure refers to the thickness of the wall, which would represent that this wall is unbreachable.35

Regardless of which of the three positions is correct, the one thing that all exegetes agree on is that the wall conveys a non-linguistic message of grandiosity. The grandiosity of the wall (and by association the builders of the wall) is also present in the materials in which the wall is built (jasper) and the various type of jewels embedded in the wall. This follows other description of a bedazzling new or refurbished earthly Jerusalem.36

The gates as an element of territorialization/deterritorialization

The walls have a very important sub-element, the gates.37, 38As any other city gate, the gate of the city have a territorializing or deterritorializing agency on the assemblage as they can either allow external elements to come in or be excluded from the assemblage. In the same spirit of the bling-bling fest of the city and the walls, the gates of the city are described as pearls. The gates are also a status symbol.

Besides the pearly description of the twelve gates, the gates are described as permanently open. Who are then supposed to come through those permanent open doors? According to the narrative “the Kings of the earth, the people will bring their glory to New Jerusalem39. The reference to Nations, Kings and People, becomes a serious plot-hole. According to the previous chapters, the kings of the earth and the nations were annihilated in the Beast’s battle against the Lamb at the end of Chapter 19 and in the Battle of Armageddon.40 Where do these kings and nations come from?

The fact that the gates are permanently open render the wall nothing more than a “show of money”, conspicious consumption that has no other function but to impress others through the exhibition of prestige and power.41 The permanently open gates have provoked theologians and biblicist as diverse as Keller, Koester, Xabier Pikaza and others others to proclaim an utopia where all are welcomed. Keller argues; “The many peoples and kings suggest a pluralism at once ehtnic and political, moving with the dignity of their differences through the ever open gates.”42

The New Jerusalem’s city walls are a perfect example of territorialization, both physical and non-physical. The gargantuan size of the walls of the New Jerusalem is a signal of a quantum territorialization of the New Jerusalem assemblage. Yet, any territorialization is nullified by the fact that the gates of the city are never shut. The ever open gates turn the potential quantum territorialization on its head creating a process of deterritorialization.

Still, there is still an element that may potentiate territorialization, the fact that in each of the gates there is an angel.43 What is the function of these angels at the gates? Are they manning tourist information booths for the pilgrims or are they angelic bouncers? Angels at the gate should evoke the tale of Genesis 3 where an angel is stationed at Eden so that Adam, Eve and their descendants would not sneak back to the garden and eat from the tree of life.44 This connection with Genesis can be established by the fact that inside the New Jerusalem is the tree of life.45 Other traditions relating to a new or refurbished Jerusalem also talk about angels or sentries at the gate. Koester explains;

Some interpreters think they also prevent evildoers from entering (Rev 21:27), as gatekeepers did in the earthly Jerusalem and its temple (1 Chr 23:5; 26:1–9; Neh 3:29) and as Isa 62:6 says, “Upon your walls, O Jerusalem, I have posted sentinels.” The LXX identified the sentinels as guards, and later tradition construed them as angels, like those said to control the heavenly gates (Exod. Rab. 18:5; Mart. Asc. Isa. 10:27).46

Rather than guards or sentinels, Koester goes on to argue that these angels mearly serve as symbols of the of the presence of God. His position is based on the fact that before the descend of the New Jerusalem the wicked have been banished and Satan has been sent to the lake of fire. Evil no longer exist. Other interpreters such as Gordon E. Fee and Brain K. Blount agree with this assessment. We are not completely convinced.

John of Patmos is very clear in making a distinction between God and the angels. The most clear cut distinction can be seen in Revelation 22:8-9, when the revealing angel rebukes John for attempting to worship it. It is unlikely then that the angels of the gate would serve as place-holders of the presence of God. Then what is the best hypothesis of the function of these angels?

The divine Buckinham Queen’s Guard function is built on the premise that since evil has been vanquished, there is no need to guard the gates. Aune, is not quite convince that this is the case.47 Afterall, Revelation 21:27 says that “But nothing unclean will enter it, nor anyone who practices abomination or falsehood, but only those who are written in the Lamb’s book of life” The only way in which this prohibition makes sense is if there is a possibility of happening.

Imposible behaviors are not outlawed. Although evil has been eradicated, there is at least the possibility of defilement of the New Jerusalem (nothing unclean will enter it). So how to prevent uncleaniless from entering an ever open gate, by putting an angelic bouncer at the gate, of course.

So it seems we webbed ourself into a sticky entanglement. First, we described a literally out of this world city wall, which clearly is a territorializing element. But we also found that this wall is in fact porous. The ever open gates where the peoples and the nation come through cancels the territorialization and in fact begins a process of deterritorialization, where heterogeneous external individuals can come into the city. But at the end we find out that the gates are not really open for everyone, for there are angels in the gates to prevent any contamination. This swings the pendulum back to territorialization.

The territorializing/deterritorializing back and forth should not to be viewed as a fatal flaw or plot hole in our application of assemblage theory to the New Jerusalem. Ruth M. Van Dyke clarifies that:

Deterritorialization and reterritorialization are always relative, always connected, always in motion. There are some similarities here with the Marxist concept of dialectical tension, but without the implied limitations of two opposing poles.

Assemblages are simultaneously, constantly, multi-dimensionly pulling (and being pulled), pushing (and being push), gathering (and being gathred), resisting (and being resisted).48

This paves the way to clarify that in true Derridian fashion, we must resist the tendency to pose territorialization and deterritorialization as binaries opposites. Assemblages are complex and they must not be caricatured, nor simplified by binaries. In an assemblage an element can have a territorializing effect, a deterritorializing effect or both. In assemblages there is no Newtonian third law of motion (for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction). Rather what we have is a push-pull-gather-scatter dynamic.

Conclusion

Since it descended from the stylus of John of Patmos, the New Jerusalem has captured Christianity’s hope for a better world. This tropos needs to be explored to ascertain how it has shaped our values, attitudes and beliefs. We contended that New Materialism and the various analytical tools related to it can be an effective approach to do just that. We have one of the analytical tools of new materialism and delineated a path of how would a new materialist analysis of the New Jerusalem would look like. Obviously much would need to be done. For example, for the lack of space we have not touched upon the coding/decoding dynamic of the New Jerusalem. Also, each of the other elements that we propose could be explored in terms of what role they play and how they territorialize/deterritorialize the New Jerusalem.

Other possible analytical tools that may have some tangency with New Materialism could be explore (the affect-rich-geography of Nigel Thrift, the materialism of Jane Bennett, the quatum physics of Karen Barad, etc.). Quite frankly, the possibilities of fruitful entanglement with new materialism and the New Jerusalem as big as the walls of the city.

1 This article is an adaption of a research paper submitted for the course Earth Matters: Religion and the New Materialism given by Dr. Catherine Keller during the Spring of 2021 in Drew University.

2 Louis Wirth, “Urbanism as a Way of Life,” American Journal of Sociology 44, no. 1 (1938). 5

3 Timothy R. Pauketat, “Introducing New Materialisms, Rethinking Ancient Urbanisms,” in New Materialisms, Ancient Urbanisms, ed. Susan M Alt and Timothy R. Pauketat (New York, NY: Routledge, 2020). (Kindle edition) 4 Pauketat, “Introducing New Materialisms, Rethinking Ancient Urbanisms.” (Kindle edition)

5 Wirth, “Urbanism as a Way of Life.” 8

6 Robert E Park, “The City, Suggestions for Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment,” in The City, ed. Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1967).1

7 Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter; A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010). xiii 8 New Materiallisms is a recent onthological approach that argues that “… materiality is always something more than “mere” matter: an excess, force, vitality, rationality or difference that renders matter active, self-creative, productive, unpredictable. In Sum, new materialist are rediscovering a materiality that materializes, evincing

immanent modes of self-transformation that compel us to think of causation in far more complex terms; to recognize that phenomena are caught in a multitude of interlocking systems and forces and to consider anew the location and nature of capacities for agency.” Coole, Diana and Frost, Samantha “Introducing the New Materialism” in New Materialisms; Onthology, Agency and Politics ed. Diana Coole and Samantha Fox (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010) 9

9 New Materialisms Ancient Urbanism, ed. Susan M. Alt and Timothy R. Pauketat (New York, NY: Routledge, 2020).

10 Indeed, Fustel de Coulanges argues that religion is in fact the genesis of cities. Fustel De Coulanges and Numa Denis, The Ancient City: A Study on the Religion, Laws and Institutions of Greece and Rome (Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books, 2001). 104-108

11 Revelation 21 and 22.

12 Martin, Thomas W. “The City as Salvific Space: Heterotopic Place and Environmental Ethics in the New Jerusalem,” Society for Biblical Literature, 2009, accessed 4/21/2021, https://www.sbl- site.org/publications/article.aspx?ArticleId=801.

13 Catherine Keller, Facing Apocalypse; Climate, Democracy and Other Last Chances (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2021). 174

14 Thomas Nail, “What is an Assemblage?,” SubStance 46, no. 142 (2017).

15 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

16 Manuel DeLanda, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity (London, England: Continuum, 2006)., 3

17 We are aware of the many criticisms that De Landa’s elaboration of assemblage has received from theorists such as Ian Buchanan and Thomas Nail. While acknowledging these criticisms, we will continue to use De Landa’s assemblage theory as our working theory for this paper.

18 De Landa has attempted to apply assemblage theory to topics as varied as non-linear dynamics, chaos theory and artificial life. Rhys Price-Robertson and Cameron Duff, “Realism, Materialism, and the Assemblage: Thinking psychologically with Manuel DeLanda,” Theory & Psychology 26, no. 1 (2016).

19 DeLanda, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. 3

20 DeLanda, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. ibid

21 This is precisely one of the main points of contention of the critics of De Landa. They argue that a theory of assembly can be found in the deluzian-guattarian canon, specifically in A Thousand Plateaus. See Ian Buchanan, Assemblage Theory and Method: An Introduction and Guide (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020). 2-6 and Nail, “What is an Assemblage?.” 21

22 De Landa, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity (London, England: Continuum, 2006).13

23De Landa adds a third dimension in which there is a process where the identity of the assemblage is either consolidated or flexibilized through expressive media. De Landa refers to this as coding/decoding. DeLanda, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity.19

24 Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1992).

26 Inspired by the famed city walls of our home town, San Juan, PR,

27 Stephen D. Moore, “Beastly Boasts and Apocalyptic Affects: Reading Revelation in a Time of Trump and a Time of Plague,” Religions 11 (2020). 10

28 David E. Aune, Revelation 17-22, vol. 52C, Word Biblical Commentary, (Dallas, TX: Word Incorporated, 1998). Digital Edition

29 To illustrate how city walls functions as status symbols we can point to the book of Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible, where Nehemiah’s grievance to the Persian king is that the walls of Jerusalem had not been rebuild. This was clearly an affront to Nehemiah’s and his people’s honor. Nehemiah 2:1-5. See also Nehemiah 2:17; 1 Maccabees 4:60, Isaiah 26:1, Josephus’ Jewish Wars 5.142-48a

30 Craig R. Koester, Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, ed. John J. Collins, vol. 38A, Anchor Yale Bible, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014). 814

31 Revelation 21:12-15, 17-21

32 Or the walls that separate Palestinians from Israeli settlements or the wall proposed by the government of the Dominican Republic to prevent Haitians from crossing the border.

33 Koester, Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. 816

34 Brain K. Blount, Revelation: A Commentary, ed. C. Clifton Black, M. Eugene Boring, and John T. Carroll, 1st ed., The New Testament Library, (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2013). Digital Edition

35 Aune, Revelation 17-22. Digital edition

36 Isaiah 54:11-12, Tobit 13:16 and the New Jerusalem texts from the Dead Sea Scrolls

37 Revelation 21:12-13, 21

38 We cannot overstate the importance of city gates in the ancient world. As Daniel A. Frase comments in the introduction to his book about city gates in ancient Israel; “The gate complex of an ancient Israelite city was more than a mere passage into the town, or a defensive military structure. It was the civic forum, the heart of the city. The open spaces of the gate complex hummed with activity: the town’s elders oversaw legal procedures, kings publicly sat and took counsel, and prophets proclaimed their messages of doom. Townspeople came and went, bought and sold, worshipped their deities, were tried and executed. Indeed, most of a town’s civic life was centered on the town gate complex. And because of the prominence of gates within the culture, they took on additional significance: gates were symbolic of royalty and independence, of community well-being, of metaphysical boundaries, and of Israelite society itself. For hundreds of years, gate complexes stood as an institution central to the Israelites’ social identity, shaping how they interacted with their neighbors, how they governed themselves, how they went to war, and how they perceived themselves.” Daniel A. Frese, The City Gate in Ancient Israel and Her Neighbors: The Form, Function and Symbolism of the Civic Forum in the Southern Levant (Leiden, The Netherlands: Kononklijke Bill NV, 2019).1

39 Revelation. 21:24-26

40 Aune, Revelation 17-22. Digital Version

41 See Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, ed. Martha Banta (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007).

42 Keller, Facing Apocalypse; Climate, Democracy and Other Last Chances. Kindle edition

43 Revelation. 21:12

44 Koester, Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. 814

45 Revelation. 22:2

46 Koester, Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. 814

47 Aune, Revelation 17-22. Digital version

48 Van Dyke. Ruth M., “Experience and Assemblage in the Ancient Southwest,” in New Materialism, Ancient Urbanism, ed. Susan M Alt and Timothy R. Pauketat (New York, NY: Routledge, 2020). Kindle edition